The amazingly “grippy” toes of geckos have inspired a new approach to cancer therapy that could lead to fewer side effects and better outcomes for patients.

This is the conclusion of a study by researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder, who have developed a material that can stick fast to tumors inside the body and release chemotherapy drugs—even in difficult-to-treat cases.

Bladder cancer, for example, is a common condition—the American Cancer Society estimates there will be around 84,870 new cases of the disease in the US this year, resulting in some 17,420 deaths—and yet it is also uniquely challenging to treat.

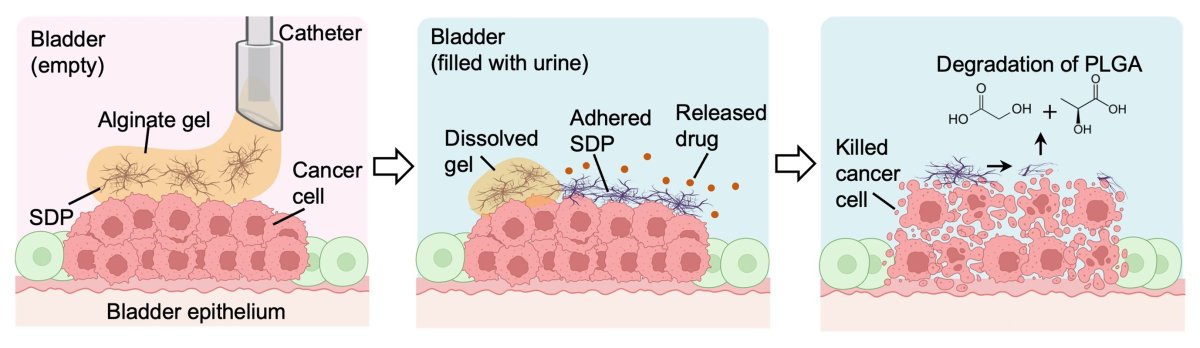

Doctors insert a catheter into the bladder to bathe the organ in chemotherapy drugs—but this medication gets flushed out every time the patient urinates, and side effects are common as the drugs end up getting in healthy tissue as well as the target tumors.

The sticky material cooked up by the team, meanwhile, could be applied to the tumors specifically—and remain there even if the patient urinates.

“We envision that this gecko-inspired technology could ultimately reduce the frequency of clinical treatments, potentially allowing patients to receive fewer but longer-lasting therapies,” said paper author and chemical engineer Jin Gyun Lee in a statement.

Anna-av/Getty Images

The structure of the gecko’s toes have inspired many a previous product—from special superglues through to ‘spiderman’-style climbing suits—but such have long proven difficult to emulate in medical and personal care products.

In their study, Lee and colleagues set out to create a material that was not only sticky, but could also linger in the body to deliver a sustained dose of medicine before safely disintegrating—and all while minimizing the impact on healthy tissue.

“Our goal was to create an adhesive biomaterial that could safely adhere to bladder tumors and release drugs over multiple days,” paper author and CU Boulder biochemical engineer professor Thomas F. Austin told Newsweek.

“While many chemical adhesives exist, we were inspired by nature in that gecko’s feet can adhere to almost any surface through purely physical means.”

Jin Gyun Lee/CU Boulder

As Austin explains, the secret to the gecko’s sticky toes lie in how they are covered in microscopic bristles—known as ‘setae’—that display even smaller nanoscopic features known as spatulae.

He added: “The result is that their feet, while small, have enormously high surface areas. Realizing this, we sought to create a biomaterial that adheres to biological tissues through similar physical means by making particles with nanoscopic tendrils for safe and robust adhesion.”

The researchers managed to turn an already FDA-approved biodegradable material called poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) into small particles with branched, hair-like nanostructures similar to those on the reptile’s feet.

They then infused these particles with chemotherapy drugs and attached them to cancer cells in a petri dish and bladder tumors in mice, finding they clung tightly to the cancer for days, even in a slippery environment like the surface of a bladder.

They were well tolerated by the animals and produced a favorable immune response.

Goran13/Getty Images

More research is needed—and it could potentially be years before the technology is ready for clinical trials in people. But the researchers believe it could one day be a game changer for treating localized tumors with minimal damage elsewhere in the body.

“We believe this is a very promising first step,” said Shields.

Looking to the future, the researchers picture the gecko-inspired treatment could be delivered in the form of a gel applied directly to the tumor. The technology could also work for other cancers like oral, head or neck tumors.

And it could even offer other potentially life-saving benefits beyond that.

“While this goes beyond the scope of our study, we could envision this technology being used to adhere to other tissues accessible by endoscopy (e.g., lungs, GI tract),” Shields added.

“We could also envision this work being used as a medical plug or way to promote wound healing if loaded with the appropriate drugs. But again, more research is needed to investigate these applications.”

Do you have a tip on a health story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about bladder cancer? Let us know via health@newsweek.com.

Reference

Lee, J. G., Petraccione, J., Trese, K. A., Hughes, A. C., Ausec, T. R., Salzmann-Sullivan, M., Su, L.-J., Kim, M. T., Roh, S., Goodwin, A. P., Feng, F. X., Flaig, T. W., & Shields IV, C. W. (2025). Soft Extrudable Dendritic Particles with Nanostructured Tendrils for Local Adhesion and Drug Release to Bladder Cancers. Advanced Materials. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202505231